ESC - Slovakia -

Gerlachovský Štít

, 2655m - Info | Trip ReportHigh Tatra Day 2 :

(Day 1 was Rysy in Poland)It was Peter who dispelled the myth surrounding the wolf and the two naked maidens. The warden at Chata pod Rysmi, my guide explained as we stood admiring the unfolding panorama; the fractured, twisted ribs of rock strutting up above the clouds, liked the girls. Perhaps that's not putting it strongly enough, he liked the prettiest girls, and made sure, that at the beginning of every season he chose the prettiest of those volunteers to work in his refugee. I can vouch for his good taste. When the warden drew the chata's unique rubber stamp, the wolf was kind of a self portrait. I'm not suggesting any kind of Lycanthropy, but an imaginative sense of humour that perhaps lies a little short of today's political correctness. I judged that we had rested long enough, and motioned so that Peter continued the ascent.

Thus yesterday's great question had been answered, and I can begin again at the day's dawn. Mountain guide Peter arrived at the hostel, a charm less abode for which I paid five pound a night. We drove the short distance to Tatrankse Zruby, from where a supply track wound it's way up to Sliezsky Dom, our starting point. Only National Park vehicles are permitted to ride this narrow road, and so we clambered into the waiting green Land Rover of a National Park warden. I soon learnt that we would not be alone on Slovakia's highest mountain. Another guide was leading a party of three Czechs, a man and two women, on the same route. Huddled, and facing each other on the Land Rover's benches, I introduced myself and quickly made friends in a mixture of English and what I call Slav. Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Serbs, the Polish and Russians all have their own languages with many different words. But they all Slavic at route and it has been my experience that those of one nation can usually understand the meaning of others if they so wish. It is the wishing so that often intervenes.

Arriving at the Sliezsky Dom, we paid the small "taxi" fee and prepared for the day ahead. For me this meant depositing my unnecessary luggage with the refuge staff. I had tight schedule and reducing weight could only help me keep to it. That schedule being determined by a train departing Poprad for Budapest at four thirty five.

|

| The Sliezsky Dom from above Velicke Pleso |

We left the refuge as a group of six, hugging the eastern shore of the beautifully clear Velicke Pleso then surmounting the rock wall at the lake's northern end, where a stream tumbled over a moderate fall. Shortly after we crossed the stream where it fanned out into many channels amongst the rocks and turf. Here the two groups began to drift apart as Peter and myself moved ahead at a hectic rate. We gained height on ground that felt distinctly Scottish, Highland Scottish. A feeling given by the lack of a clear path, just the indented line from the passing of feet, the occasional cairn. It was so different from anywhere else I had been in the High Tatra where the trails had been broad and well marked. Distinctly un-Scottish were the chamois, a benefit from rising early and treading where only those with a registered guide were permitted.

The ground soon steepened, and we halted below a gully, snow filled and with a path leading across to the first fixed aids, a metal ladder secure in the rocks. The group re-gathered, but only momentary whilst we put on climbing harnesses and tied up for security. I did not feel that it was needed, but when money enters the equation, a guide will take no risks. Together we crossed the snow and scrambled up the rocks, using the ladders and pegs whenever required. Our progress was healthy and we talked; Peter explaining the route and telling stories. The youngest person he ever guided to the roof of Slovakia was a four year old boy. The lad was probably the youngest ever to have made the ascent and I congratulate him heartedly. For those of you reading with a twinge of disappointment, the boy was lifted up and over the more treacherous sections.

|

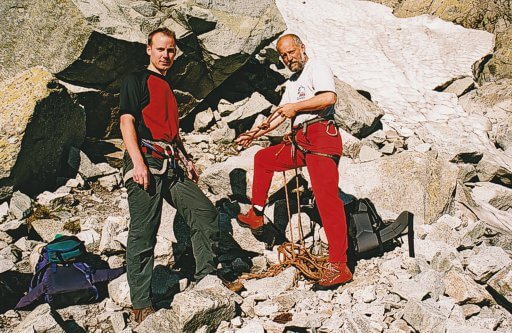

| Roping up before climbing Gerlachovský Štít. |

Gerlachovsky Štit may best be imagined as a weathered cone of rock linked by it's northern slopes to sharp and jagged ridge. The southern face of this cone has been scooped out. What remains is a horseshoe of broken teeth with high point at the northern most apex. Our route, "Velika Proba", led to a col on the eastern rim, and here I had expected to follow the ridge line, but no. Having taking photo's of the wonderful temperature inversion from which the peaks of Slavkovsky Štit and Lomnicky Štit emerged, we descended a little way into the glaciated cwm and crossed over many a broken spur until I had become quite disorientated. Looking back I found it almost impossible to identify from where we had come.

|

| Cloud inversion on ascent of Gerlachovský Štít. |

It was ten twenty by the time we reached the summit. Here we rested, soaking up the panorama of peaks and ridgelines protruding from the sinking clouds. To the west we saw Rysy, and could trace a small part of my previous day's hike. It was time to take photos, eat a little, drink and listen to other stories. Stories of the pioneering years; how, for a long time it, was believed that Lomnicky Štit was the highest mountain in the range, how Slavkovsky Štit had once been much higher but had crumbled away. And then Peter's own story. This coming weekend, he would be climbing the mountain yet again, but with no client, just friends and the press, a TV crew, etc. It will have been his five hundredth ascent and he was planning to do it in style, pioneering style with tweed suit and hooked stick.

We descended westward into the Batizovska Dolina. It was a memorable descent, picking the route that the season allowed, for there remained much snow on the valley's slopes. In places the "path" disappeared and there looked no possible way onward, the drops too sheer. But the drops were protected, the most exposed by long section of rungs requiring much care. Here I took advantage of the sling and carabineer tied to my harness, a make shift via ferrata kit, to clip onto the safety wire. More an effort to be self reliant than any distrust of Peter's rope work. With the hard part over, we glissaded over a long stretch of solid snow, a skill at which Peter was adept and I not quite so, to a view point from which the melting snow first trickled then poured over the broken crag into a stream below. We traced a pathway of sorts round and down the rock face, drank from and crossed the stream, then followed it's course through a boulder field to the blue waters of the beautiful Baizovske Pleso.

|

| Descending Gerlachovský Štít on the iron staples and chains. |

The wide and easily navigable Tatranská Magistrála passes along the tarn's southern end. This trail runs parallel to the main High Tatra ridge line and was first opened in 1937. The section we trod now, looping back eastward around Gerlachovsky Štit's southern slopes to the Sliezsky Dom, had been built much earlier. During the first world war soldiers had shifted and laid thousand of sofa sized boulders, constructing causeways and cuttings to produce a flat path way along the mountainside. These days teams of volunteers maintained the trail network and you can only be thankful.

At one o'clock the Sliezsky Dom was a hive of activity, the queues in the main bar long. I retrieved my unnecessaries from the hut's reception and joined Peter in the quieter Guide's bar for a debrief. An hour, a soup, and two pivos later, the second guide arrived, but no group. They had reached Baizovske Pleso and were making their own way back along the Tatranská Magistrála. Another hour, a pivo and a short later the three Czechs arrived and we could think about catching the Land Rover back down to the valley floor. But first a celebration was in order, for which you should read more pivo. Feeling much the worst for drink, okay let me be honest, I was totally inebriated, we set off, myself wondering how on earth I was going to catch the Budapest train in time. It was then that the two guides took the most care of me, perhaps the shared beers and the talk of Europe's Highest Peaks had momentarily endeared me to them. Peter had confessed that he too was attempting the same challenge. But back to the quick. The second guide drove us frantically to Stary Smokovec, but too late the local train to Poprad had gone. Quickly we drove onward to the next station. I'm not entirely sure, but I think we continued driving well after the road ran out, and more or less to the trackside. The electric train was almost ready to leave, I gathered my sack from the car's boot whilst Peter ran on to the track to stop the train from leaving.